More HQs Than Answers: Will Québécois Supply Meet Growing Northeast Demand?

Large new interties between Québec and both New York and New England are set to come online over the next six months, but flows on existing ties have declined in recent years. We explore whether HQ has the capacity to support the Northeast, and explore what the future might hold.

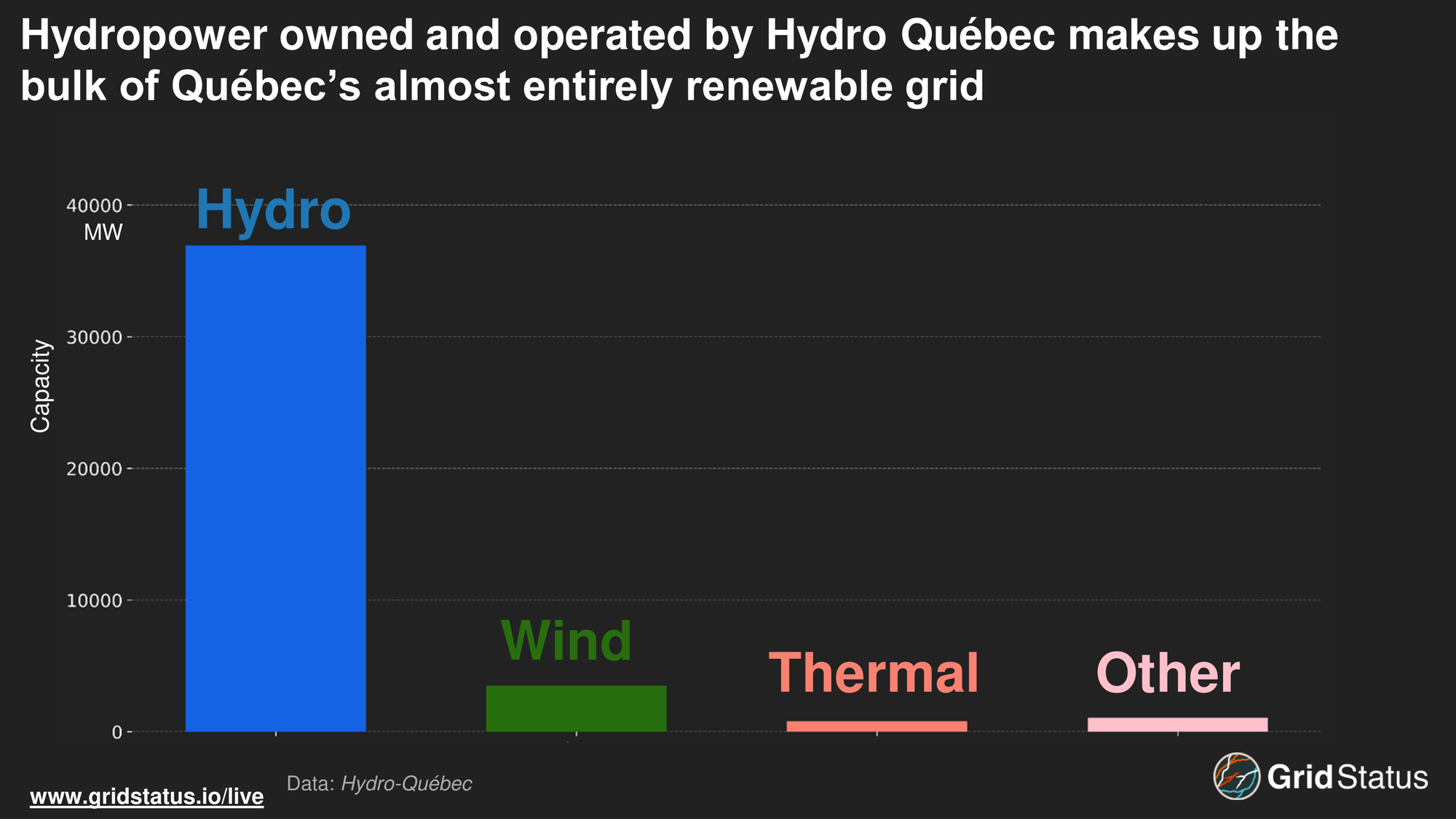

For decades, Québec has been a pivotal energy partner for the Northeast United States. Home to the cheapest and cleanest grid in North America, imports from Hydro-Québec (HQ) have enabled the natural gas-dependent Northeast to phase out coal and bolster supply in a region famously difficult for infrastructure projects. This relationship is the cornerstone of two new grid ties, both scheduled to come online over the next six months, and each considered central to the climate goals of New York and New England.

This perception of boundless Québécois hydropower has one major flaw: reality. As construction has progressed on these new transmission lines, flows across existing ties have fallen. We’re taking a look at the Hydro-Québec of today, how ties between the US and HQ have grown, and how the region's changing fuel mix is a sign of current challenges, on both sides of the border.

Check it out and let us know what you'd like to see covered!

Vieux Histoire

Stretching from the borders of New England to the vast, barren, subarctic, Québec, Canada’s largest province by land area, capitalized on one of its most abundant natural resources, rivers, as a key part of its industrialization and a cornerstone of the region’s future. Québec’s rivers have been utilized for thousands of years, first by indigenous communities that relied on the rivers for hunting and fishing, and beginning in the early 20th century, for hydroelectric power.

The HQ of today traces its modern origins to the early 1960s, when the minister of Québec’s Provincial Natural Resources, René Lévesque, pushed for a transformation of its small, existing utility as well as the entire province's electric grid. Under the premiership of Jean Lesage, often viewed as the father of modern-day Québec, Hydro-Québec was nationalized and began acquiring and consolidating disparate local distribution companies, growing into the province-wide behemoth it is today.

This expansion laid the groundwork to support Québec’s industrialization, bringing economic and demand growth. Today, Québec’s economy is highly diversified, with a strong tech sector as well as traditional industrial activities, particularly in manufacturing. In 2025, this confluence of cheap power and tech talent attracts further demand growth, with data centers now contributing to the province’s load growth story as well. Internal demand, external deals, and aging infrastructure have come together to challenge HQ and necessitate the expansion of Québec’s hydroelectric fleet.

Comment tu utalise?

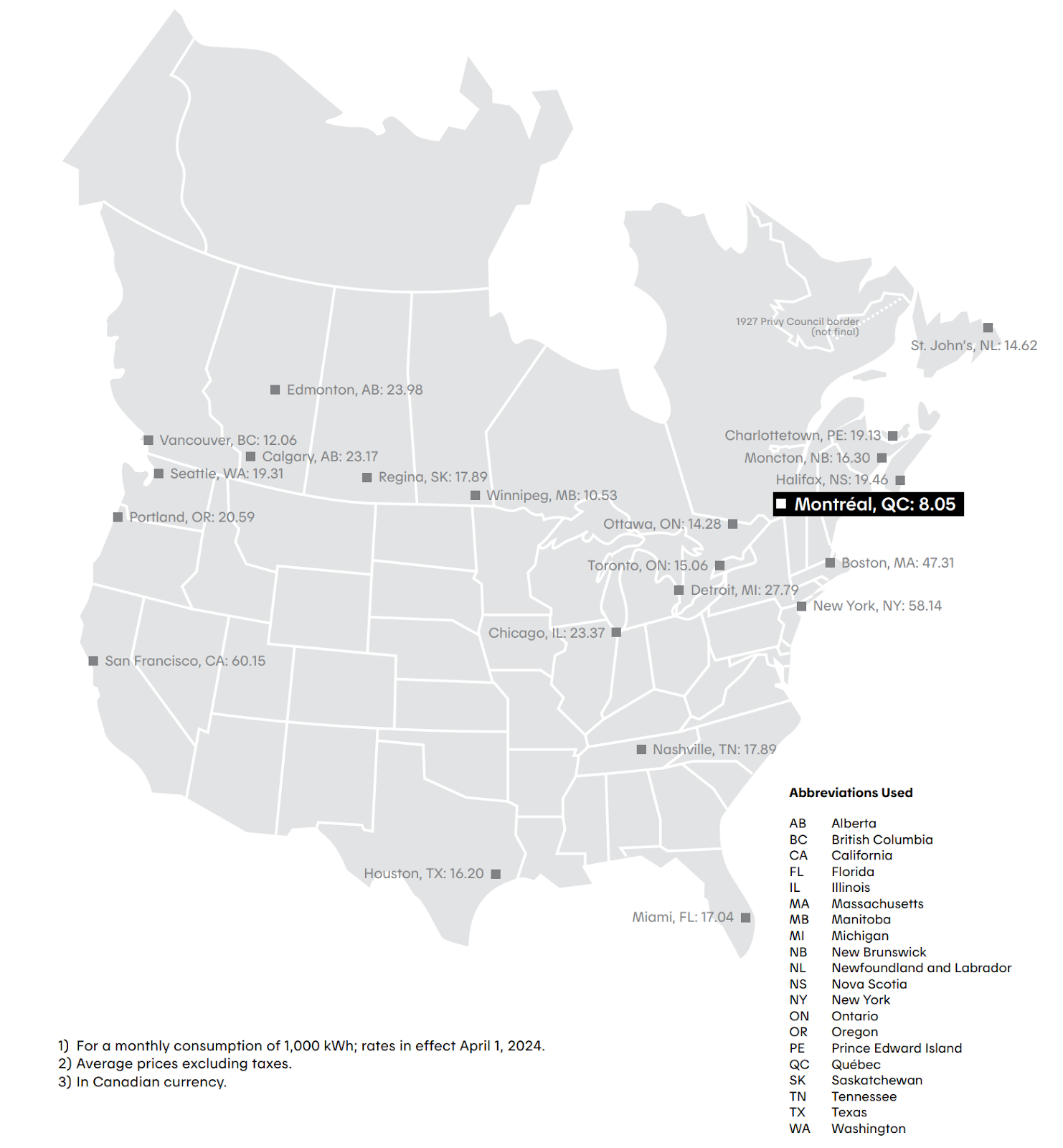

Québec’s fuel mix allows the utility to have some of the lowest and most stable utility rates in North America. In a 2024 report, HQ compared its residential and industrial rates to those of other major North American cities. Residential consumers, on average, paid 8.05 cents (CAD) per kWh, three times less than in Chicago, whereas large consumers paid 5.74 cents per kWh, half of the rate in Chicago. This cheap power and the regional climate have even influenced Québec’s load curve.

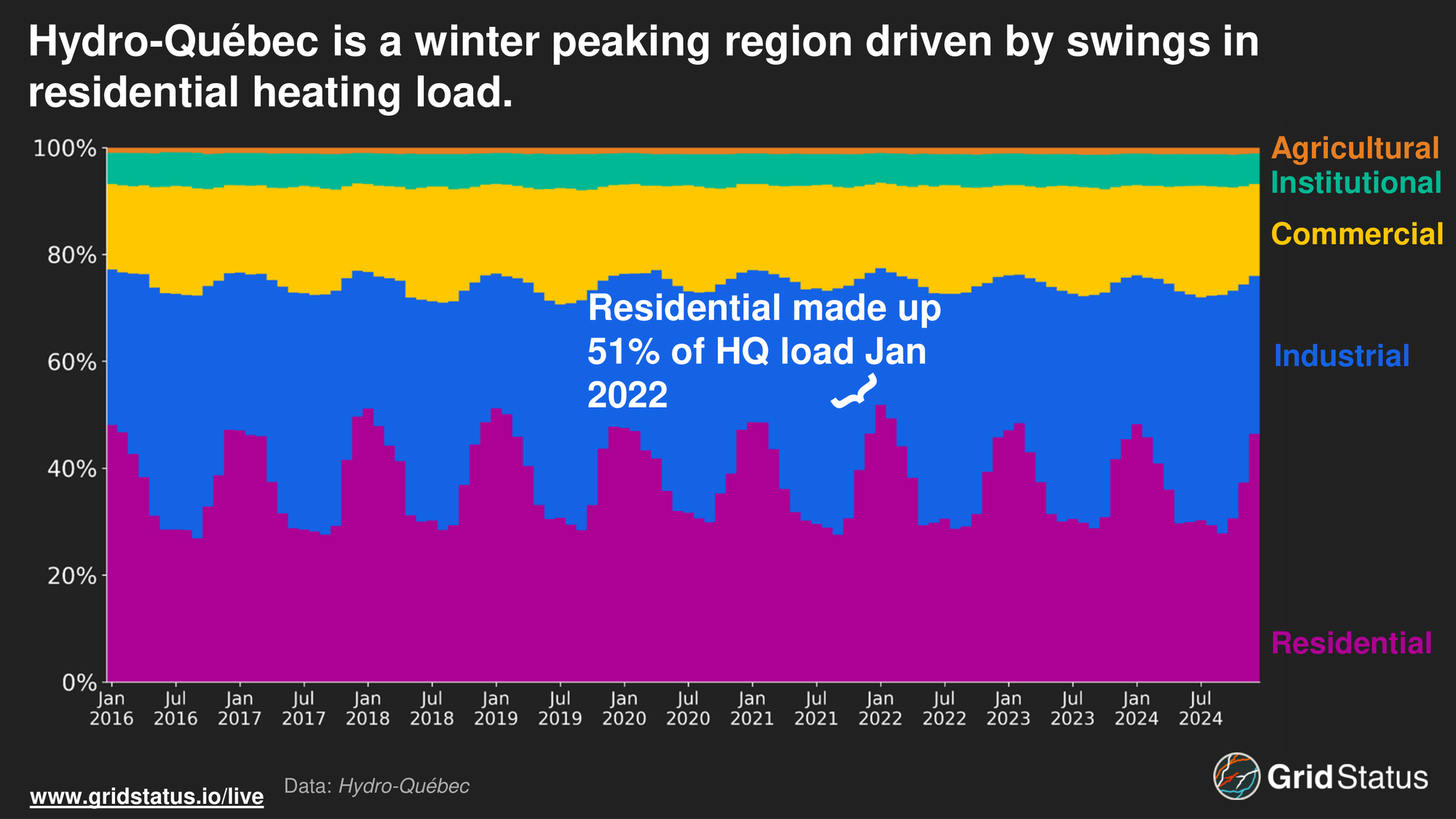

Unlike all major US power markets today, Québec is a winter peaking region. The major contributing factor is electric heating, enabled by HQ’s low rates.

Unlike more expensive regions to their south, rates this low do little to incentivize more efficient forms of electric heating, so Québec continues to rely primarily on energy-intensive resistive heating.

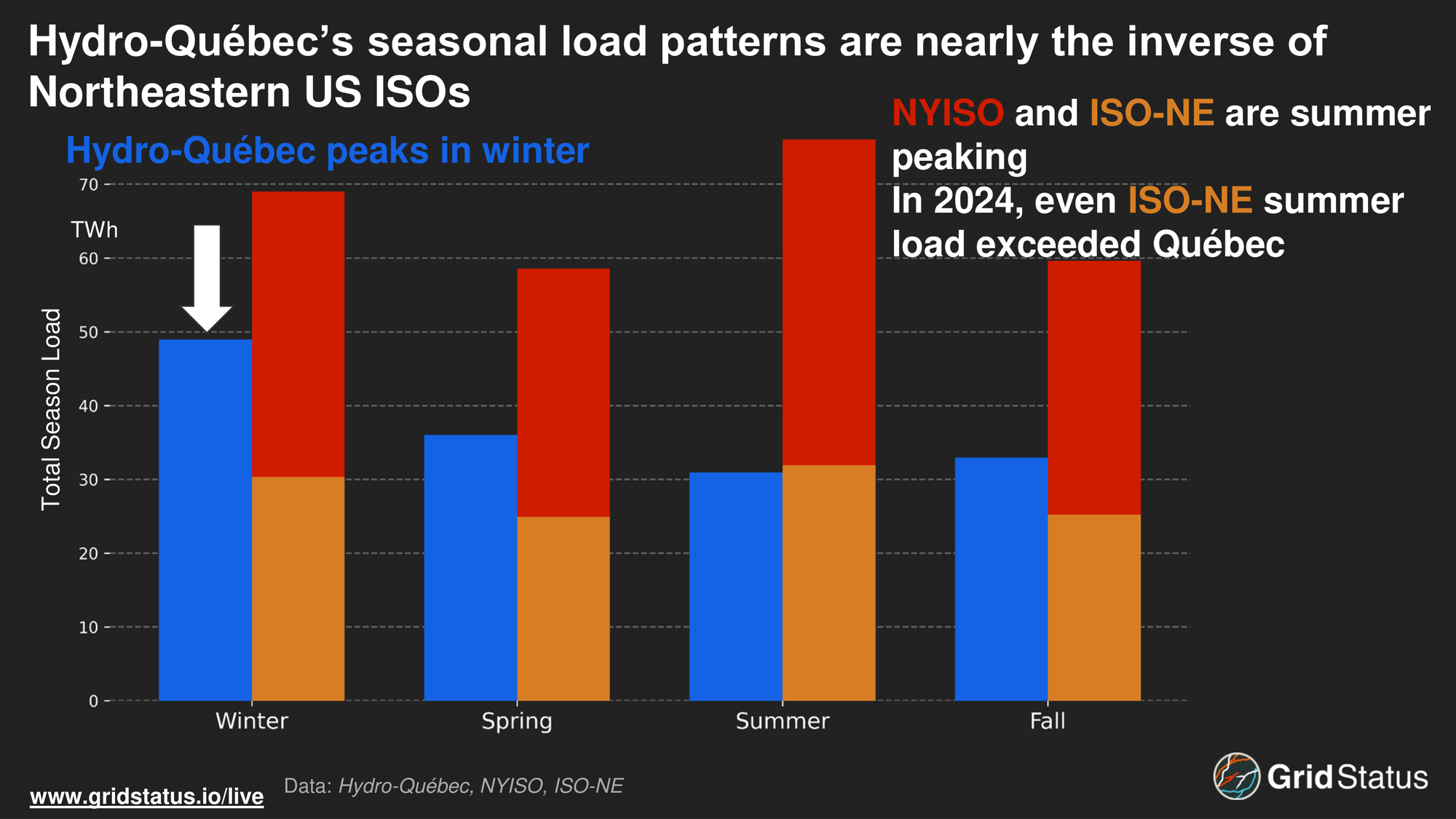

By achieving a high level of renewable generation and heating, Québec has already met many of the decarbonization goals that its neighbors, New York and New England, have yet to achieve. The impact of this was clear in 2024 when winter load levels were nearly 20 TWh higher than the summer, the opposite of nearby ISOs like ISO-NE and NYISO.

Habs and Habs Not

Québec's seasonal load patterns, abundant hydro resources, and proximity to higher cost regions made interconnecting, particularly with the Northeastern US, advantageous.

Historically, the seasonal load differences between the Northeast and Québec made these increased ties essential for mutual energy security. HQ could export into the Northeast during the summer when cooling load strains the grid. On the inverse, HQ could pull power from the Northeast during the winter when conditions tighten.

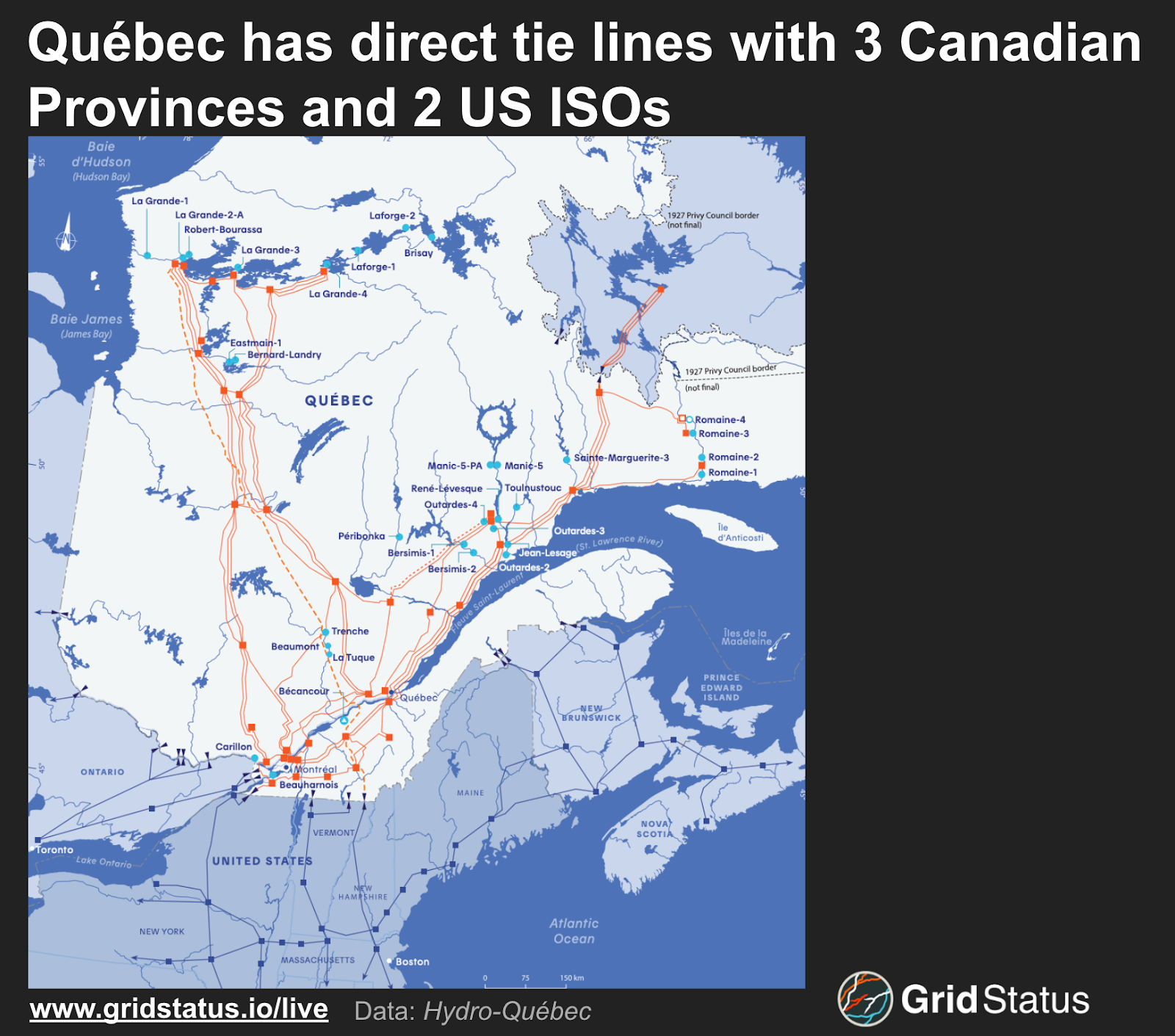

Ties between New York and Québec have existed for over a century, with the first line, Les Cèdres—Dennison, being constructed in 1914.

Besides its ties with the Northeast US, HQ has interconnected with other Canadian provinces, including Ontario, Newfoundland, and New Brunswick. While some of these ties are limited to transmission, Hydro-Québec has a long-standing, and controversial, role in the management of Newfoundland’s Churchill Falls generation station.

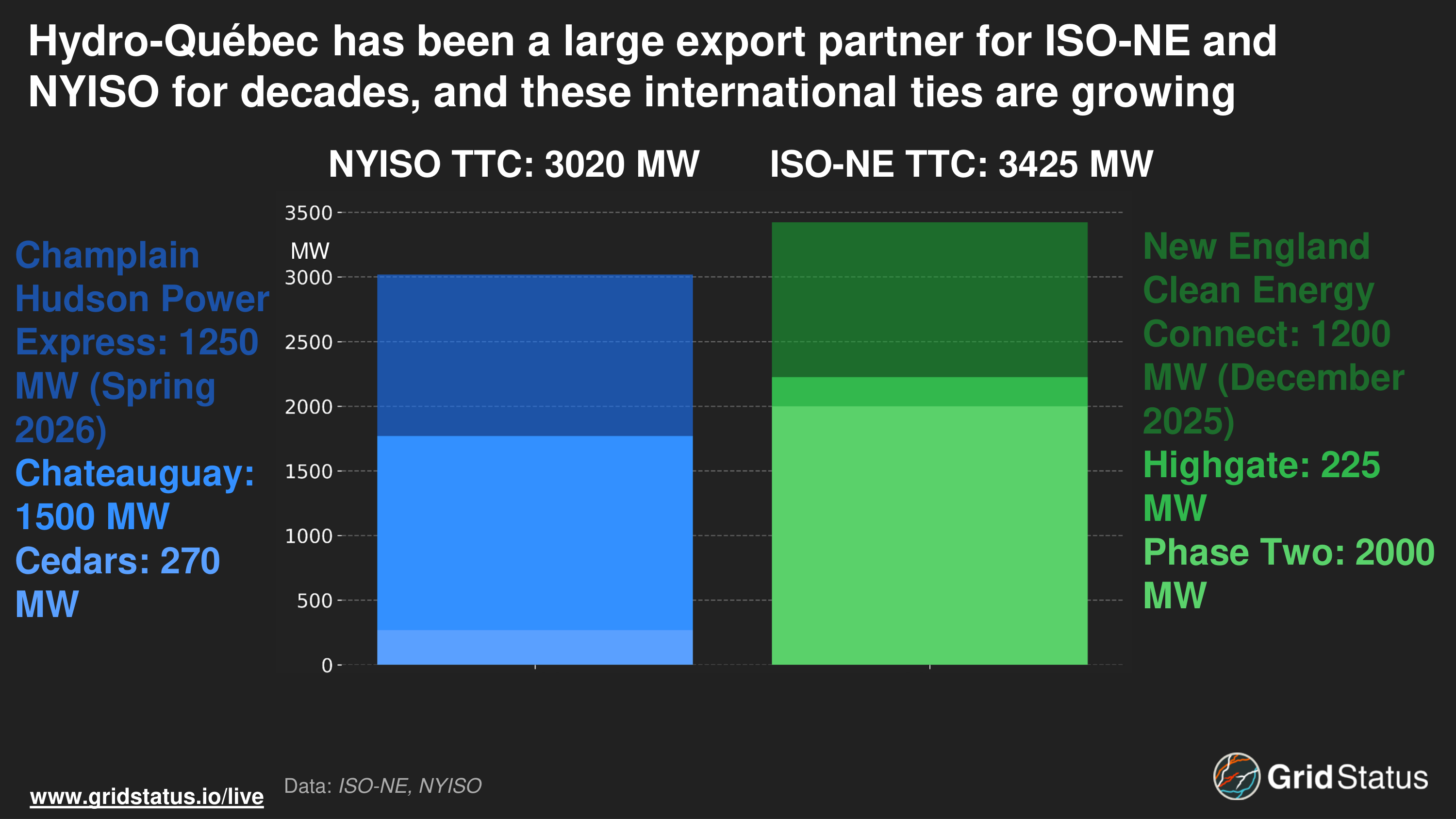

The 1980s were a decade of expansion for Hydro Québec and the Northeast markets. During this decade, HQ began its expansion into New England by constructing the Highgate DC tie into Northern Vermont. This 225 MW tie line enabled HQ and Vermont to enter into a long-term power purchase agreement, meeting nearly a quarter of the state’s electricity needs. This project was quickly dwarfed by constructing and expanding a wider DC tie line with NEPOOL, now known as Phase II. This 2,000 MW tie line, built off of an original smaller tie into New Hampshire, allows for transfers into New England’s major load center, the Boston metropolitan area at Sandy Pond.

Expansion was not limited to New England. Ties between Québec and New York grew when HQ and the then Power Authority of the State of New York established a 1500 MW DC tie line at Chateaugay.

While the 80s were the first decade of expansion, the mid-2020s are expected to be another era of increased interchange capacity with the Northeast. The New England Clean Energy Connect is expected to increase ties between New England and HQ by 1200 MW by December 2025. Additionally, the Champlain Hudson Power Express (CHPE), a DC tie into New York City (Zone J), is expected to increase total TTC (Total Transfer Capability) by 1250 MW.

Notably, the NECEC is expected to be backed by firm PPAs with Massachusetts utilities. In a FERC filing this April, outside counsel documented that utilities have signed 20-year PPAs to purchase 9.5 million MWh annually from Hydro-Québec, effectively giving the line an estimated 90% capacity factor.

If this capacity holds through the winter, imports from Québec will displace oil and gas from the New England supply stack, leading to suppressed prices and reducing pressure on the often-stretched-thin Northeast gas pipelines.

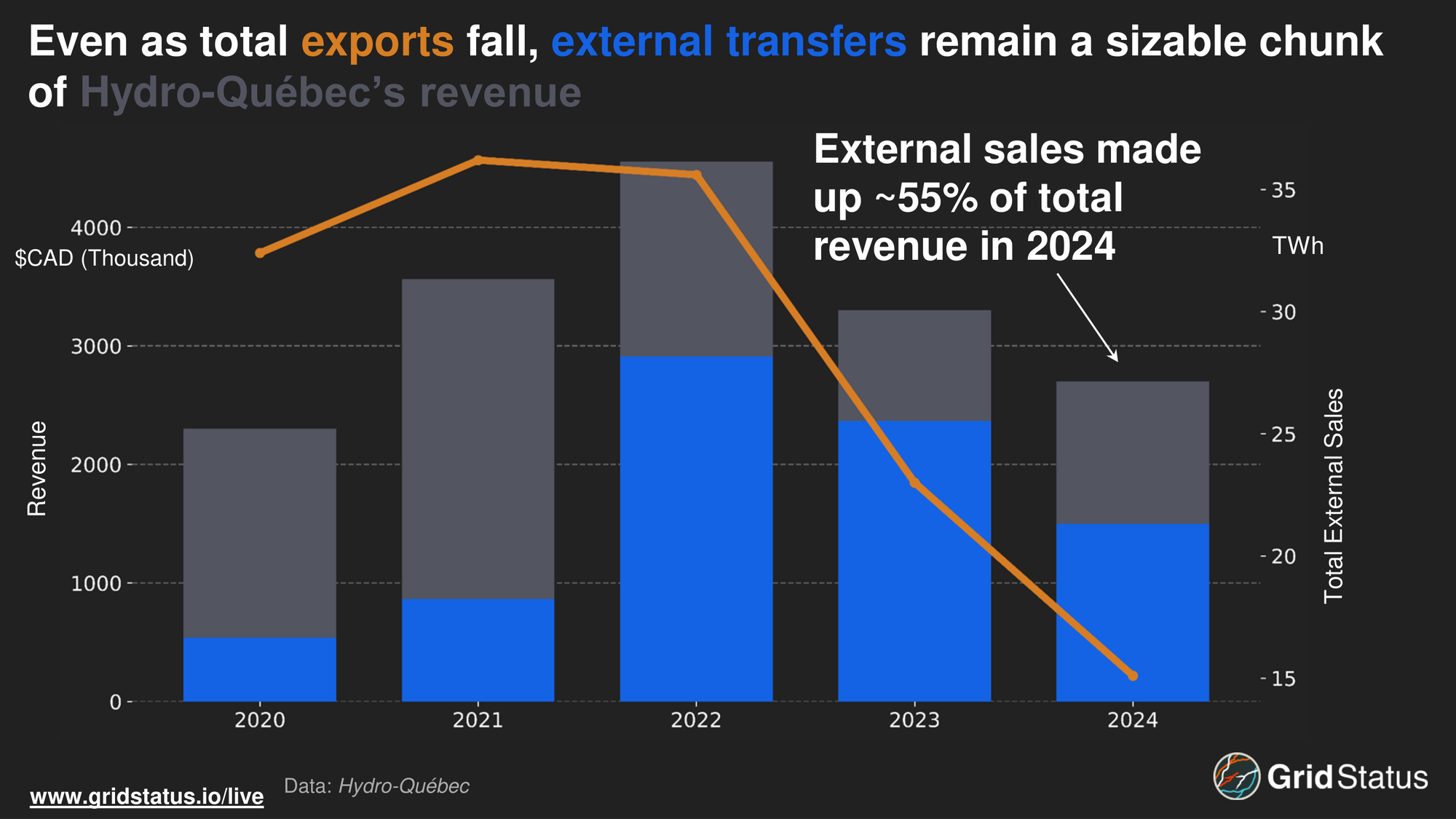

Apart from the touted energy security benefits of these tie lines, exports are a cash cow for HQ and the provincial government.

Québec's nearly 100% renewable fleet is less exposed to price spikes, which are typically driven by gas price fluctuations in the northeast. In fact, HQ is able to directly profit from the erratic nature of fuel prices by capitalizing on wholesale price volatility outside the province.

J'aime Hydro

While revenue from external transactions has remained a considerable proportion of HQ’s revenue, and as a result, a large share of the company’s dividend to its only shareholder, the Québec government, total export amounts have rapidly fallen, particularly into the Northeastern US.

These flows are, in theory, a win-win for all parties. Québec can heavily profit from external transfers while other regions can meet climate goals, and displace more expensive generation with cheaper hydro. However, this balance has been challenged in recent years.

In their 2023 annual report, HQ blamed the drop in total exports on "natural water inflows, which were well below the average recorded in the major hydroelectric reservoirs of northern Québec, on account of scant snow cover in late winter 2022–2023, lower-than-usual spring runoff, and modest summer and fall precipitation in northern Québec.” 2023 was a particularly challenging year for Québec, which, as we noted in a recent blog, experienced widespread wildfires due to drought conditions in the province, sparking a sustained stretch of imports from New York.

Québec, like many hydro-dependent regions, plays a complex game of flow and reservoir management as operators must manage inflows during the spring thaw to not only meet exports in summer (in part to capitalize on higher prices) but also conserve levels to meet seasonal load peaks in Winter, a task made increasingly challenging by drought and climate change. Effectively, HQ must balance an increasingly limited water supply to meet rising dual peaks in both neighboring regions and internally.

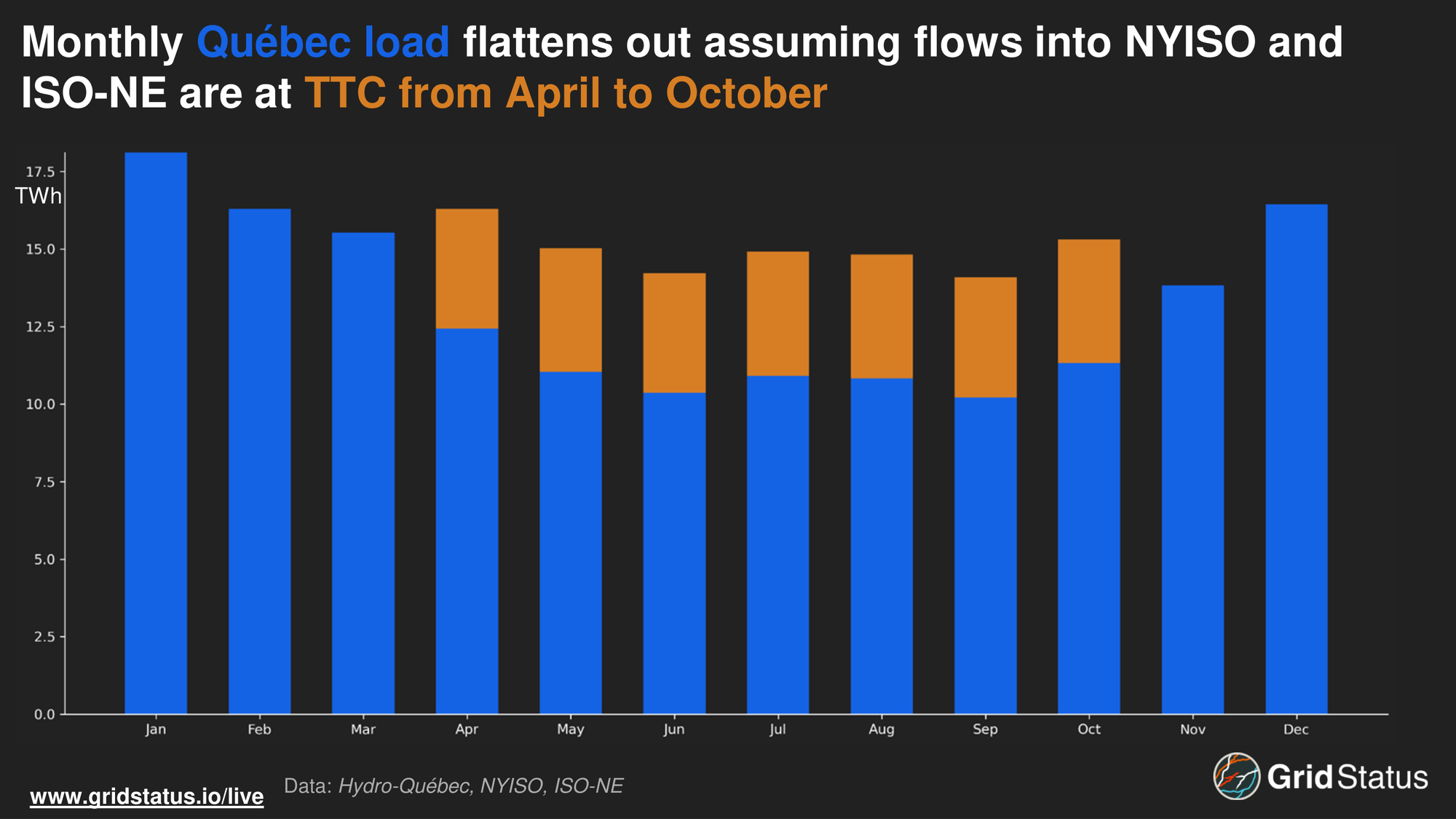

Assuming that HQ was able to export into the Northeast at its new TTC (including CHPE and NECEC) from April to October, in line with NYISO’s modeling expectations, HQ’s average monthly load flattens out.

It’s All Coming Back to Me Now

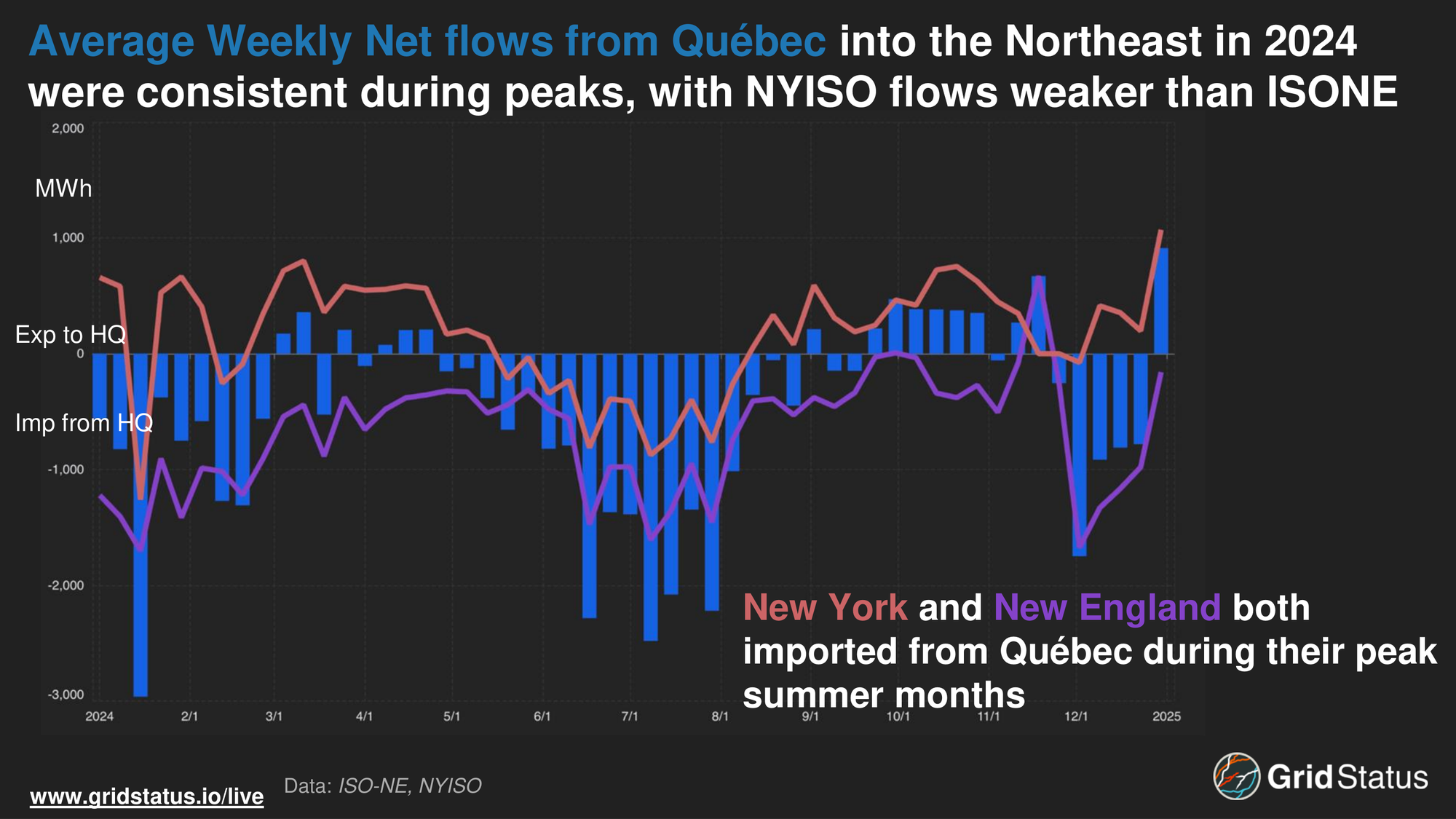

2023 was not an outlier in recent years, as total exports fell by almost another 10 TWh into 2024, and New York continued to be a net exporter to Québec for multiple months.

Flows into the Northeast were consistent during the summer months, when load disproportionately increases in the US compared to Canada, but dipped over the shoulder seasons.

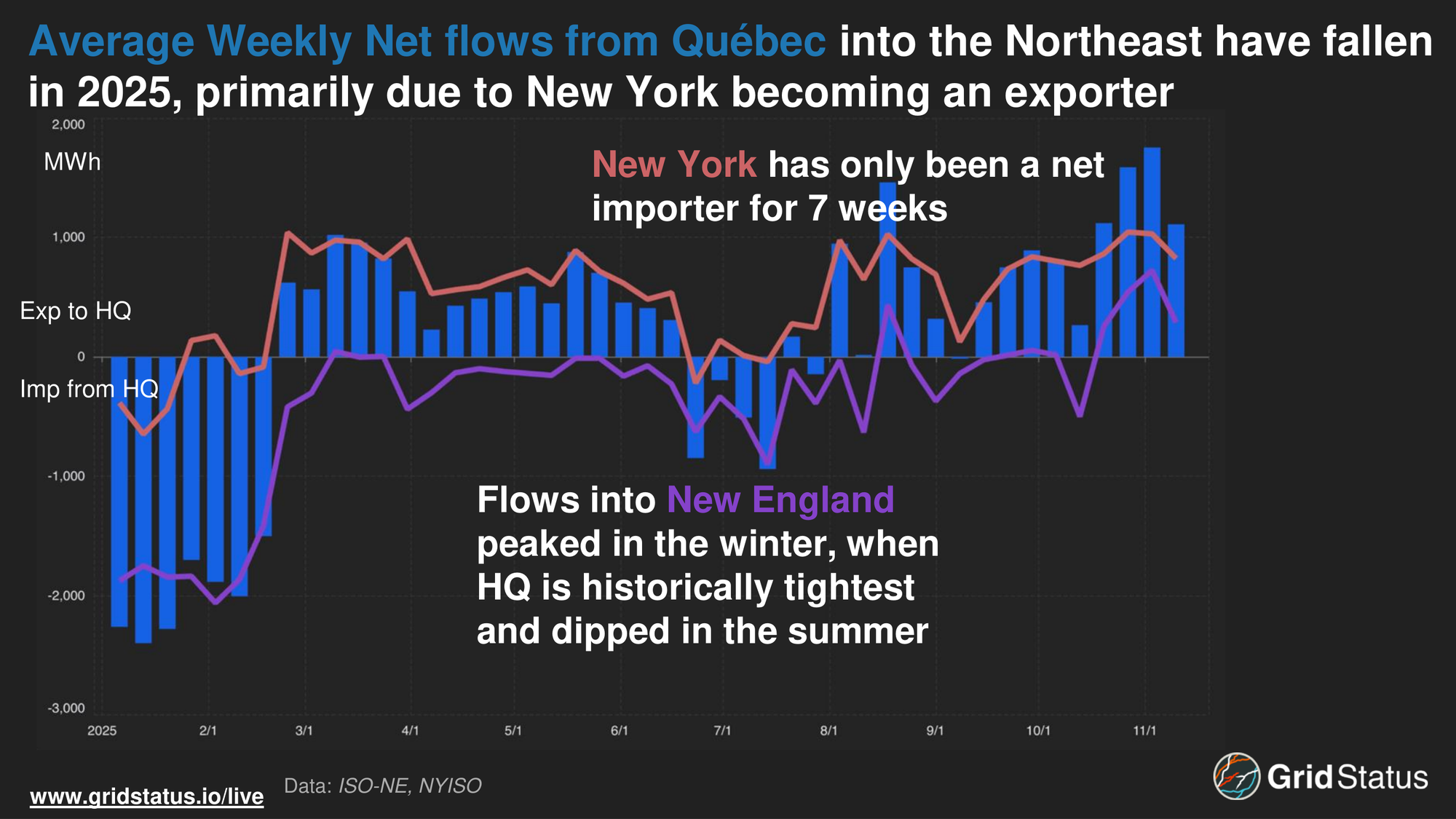

Even without odd and perhaps tariff-driven cuts to cross-border flows earlier in the year, this trend has accelerated in 2025.

Into November, New York has been a net importer from Québec for only 7 weeks of the year. NYISO’s position as a net exporter to Québec even persisted throughout most of the summer, which has historically been NYISO’s peak and HQ’s lowest demand season. One of the only summer weeks in which NYISO was importing occurred during historically widespread eastern interconnection heat. Importantly, this was not always the case.

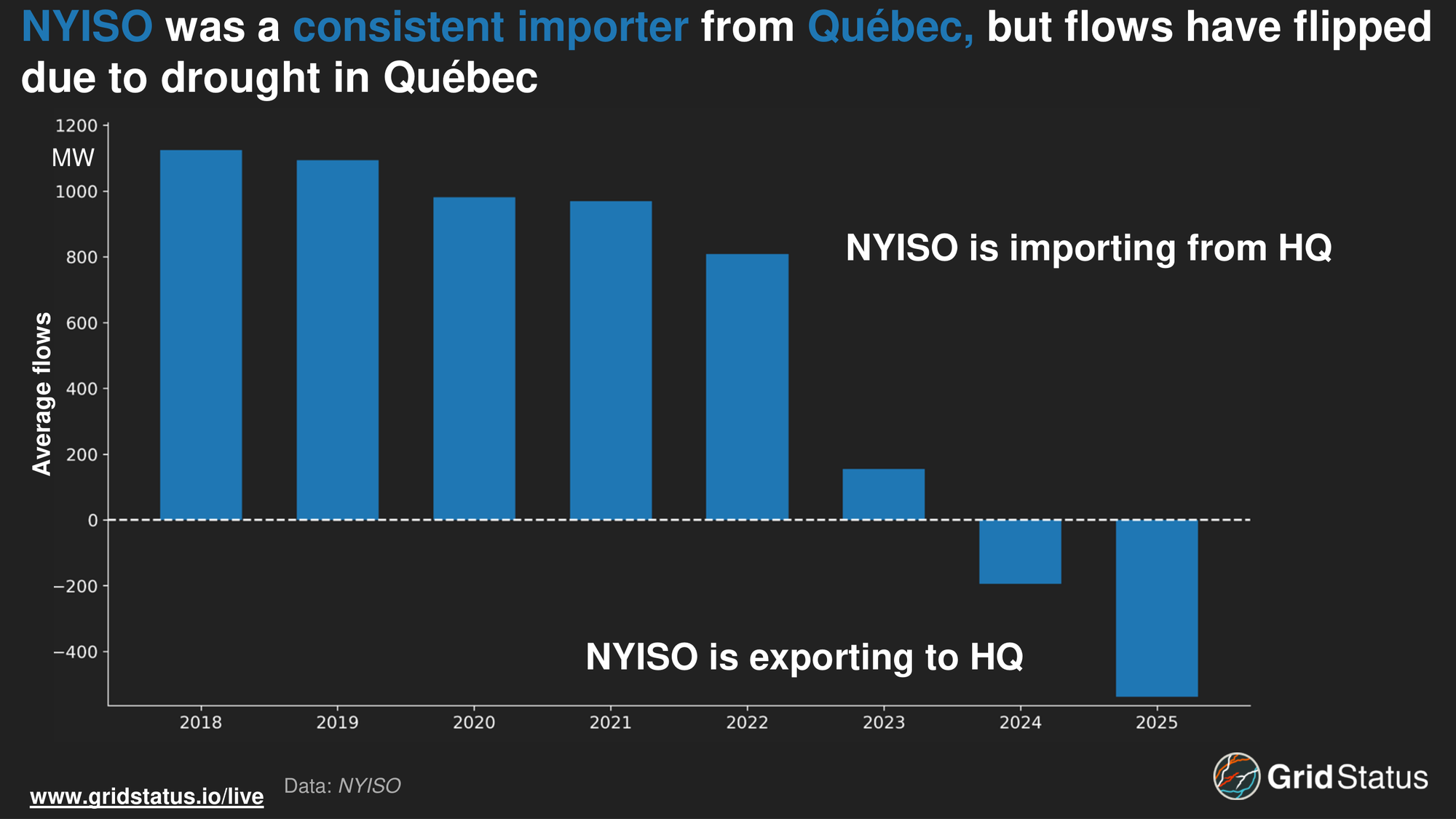

Prior to 2022, NYISO was consistently importing over 1 GW from HQ. Flows have dropped since then, with 2024 being the first year that NYISO was a net exporter to Québec.

This 180-degree shift in expectations is visible in the analysis done in support of CHPE. Back in 2021, consulting work modeled the line at a 95% capacity factor, similar to a baseload nuclear unit.

Since then, NYISO has recommended modeling in CHPE as a curtailable capacity resource in the summer, and modeling both it and all other existing HQ lines at 0 MW during the winter (November-April).

The trend of falling flows comes amidst increasingly tight grid conditions, and as both regions are forecasting sustained load growth for one of the first times in decades.

Big Dam Problems

The Northeast, and particularly New England, is expected to see margins tighten within the decade as load curves evolve, in part due to electrification efforts, particularly heating. Unlike Quebec, which electrified heating alongside its industrialization push, New York and New England have largely relied on oil and natural gas.

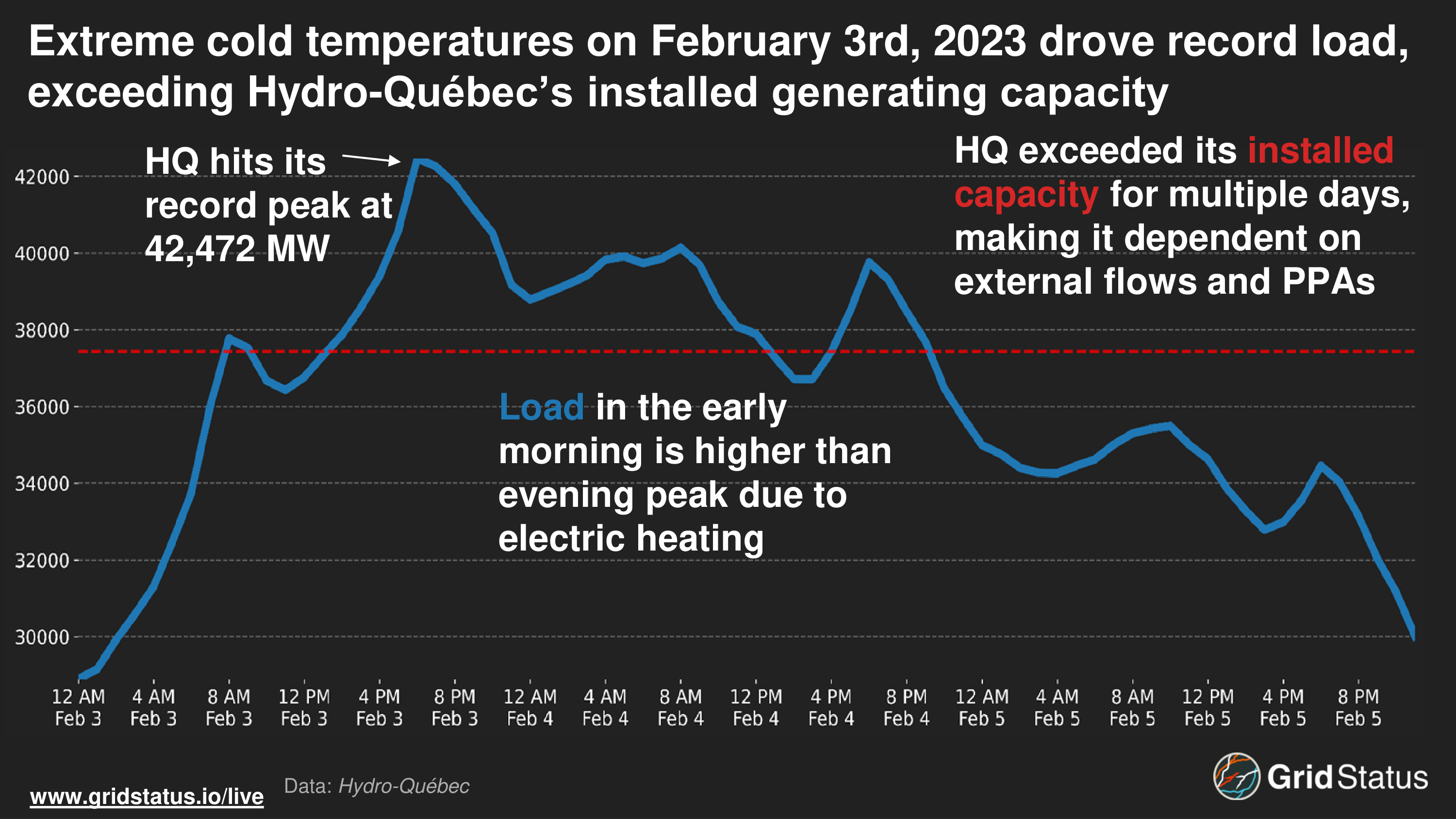

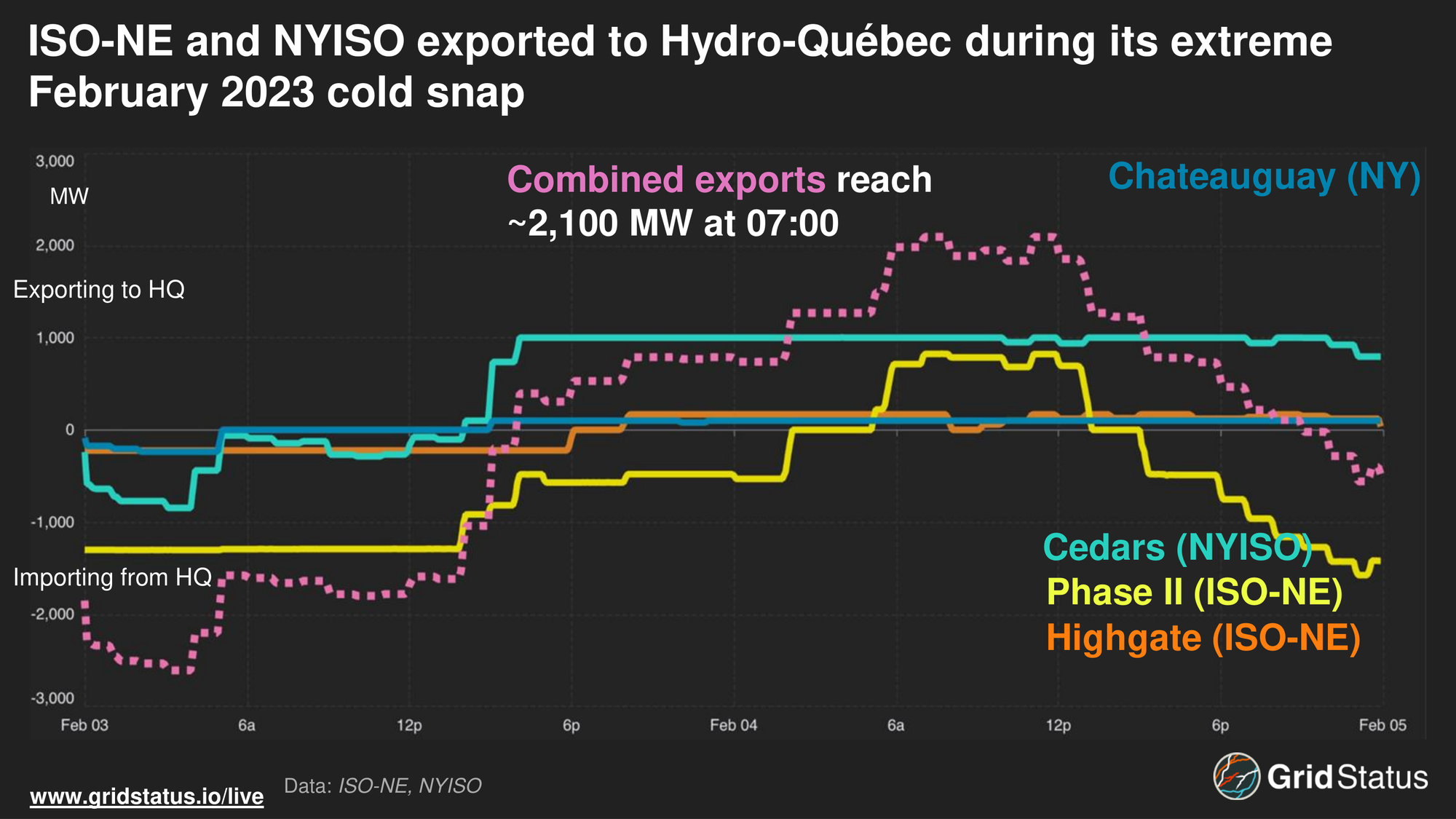

Québec's reliance on electric heating impacts its load curve. During the start of February 2023, frigid temperatures pushed into the province. While unsurprisingly, Québec sees freezing weather, this event was different as temperatures in Québec City dipped as low as -54°F.

As we have mentioned in prior blogs, electric heating has profound impacts on load in the early morning when temperatures can be coldest. This was seen in Québec when Hydro-Québec exceeded its record peak load on February 3rd, 2023, hitting well over 42.4 GW. Due to the high reliance on electric heat, load levels did subside as the sun rose, but remained close to 40 GW overnight, straining the grid as load exceeded the capacity of HQ’s entire generating fleet.

During this extreme event, Québec turned to neighboring regions and existing power purchase agreements to meet demand as heating load exceeded internal supply, including flows from the US.

While this was the case in 2023, increased strain on the grids of New York and New England may not afford similar opportunities down the line.

Both ISO-NE and NYISO are forecasted to become winter peaking as a result of electrified heating, meaning that all three regions could be seeing their annual peak at the same time.

Fortunately for HQ, ISO-NE and NYISO have both slowed their forecasted rates of electrification, and reduced federal incentives may reduce adoption.

The risks posed by Quebec’s winter peak, and how that may impact wider Northeast reliability, have already been noted by grid operators and are factored into the CHPE contract. In a July 2025 NYISO Installed Capacity Subcommittee meeting, the ISO noted that NYSERDA and HQ’s contract explicitly mentions 0 MWs of expected transfers into Zone J during the winter (November-April), and additionally that the ISO should model all other HQ ties at 0 MW during the winter.

In addition to rising demand, energy supply is increasingly a concern in both New York and New England. Both regions, particularly during the winter, see energy prices spike due to gas pipeline constraints. Without additional pipeline capacity, the regions are seeking to increase the supply of renewables, with previous planning leaning heavily on offshore wind. Complicating an already difficult build-out are federal actions, such as a stop-work order on the nearly completed Revolution Wind project and Interior Secretary Doug Burgum stating that there is “No Future” for offshore wind under the second Trump administration. While buiildouts in the Northeastern US face uncertainty, Québec is planning on increasing supply in the province, and this time not only with hydroelectric generation.

Winds of Change

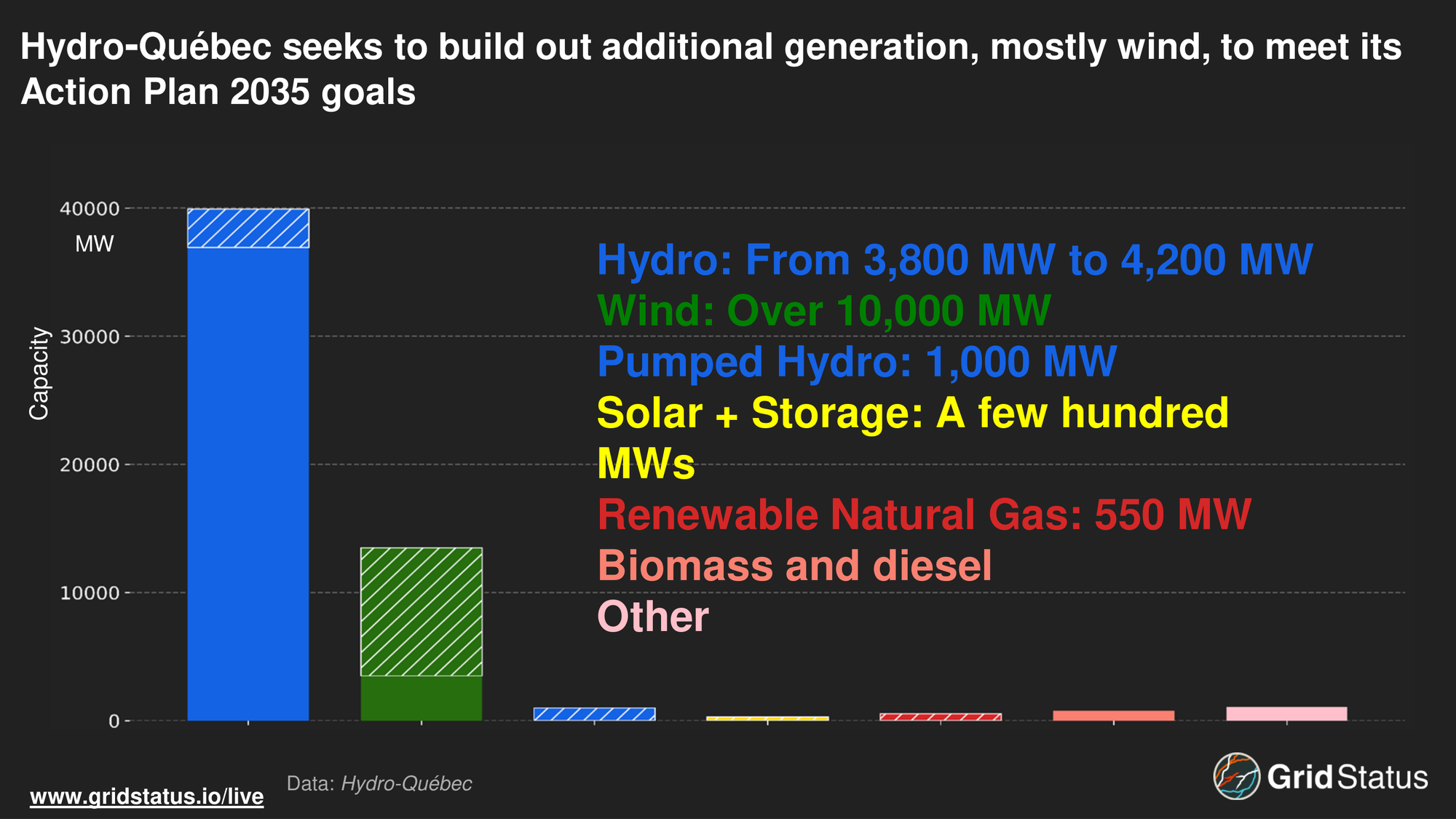

In its Action Plan 2035, Hydro-Québec laid out its expectations for further load growth and how the utility seeks to increase and diversify its generating supply.

Hydro, in the form of both uprates to existing supply and new builds, makes up a sizable portion of proposed generation, but the largest by capacity is wind. Quebec is home to some of the best onshore wind potential in Canada, and the pivot away from hydro points to the region seeking to diversify its fuel mix in the face of prolonged drought and uncertain future conditions.

A major aspect of Action Plan 2025 is meeting the goal of adding 10,000 MW of additional capacity to the grid. Similar to metrics such as Effective Load Carrying Capability (ELCC), Québec assigns wind a value of 15% of its nameplate capacity, requiring a large buildout to meet capacity goals.

The increase in internal generation capacity is spurred by Québec’s expanding load forecasts. Demand is expected to increase by 60 TWh by 2035, in part due to the province’s decarbonization goals. 75% of the increase in load is devoted to decarbonization, both electrification of transportation and further heating decarbonization, and industrial decarbonization. The remaining 25% is devoted to an amorphous “Economic Growth” category.

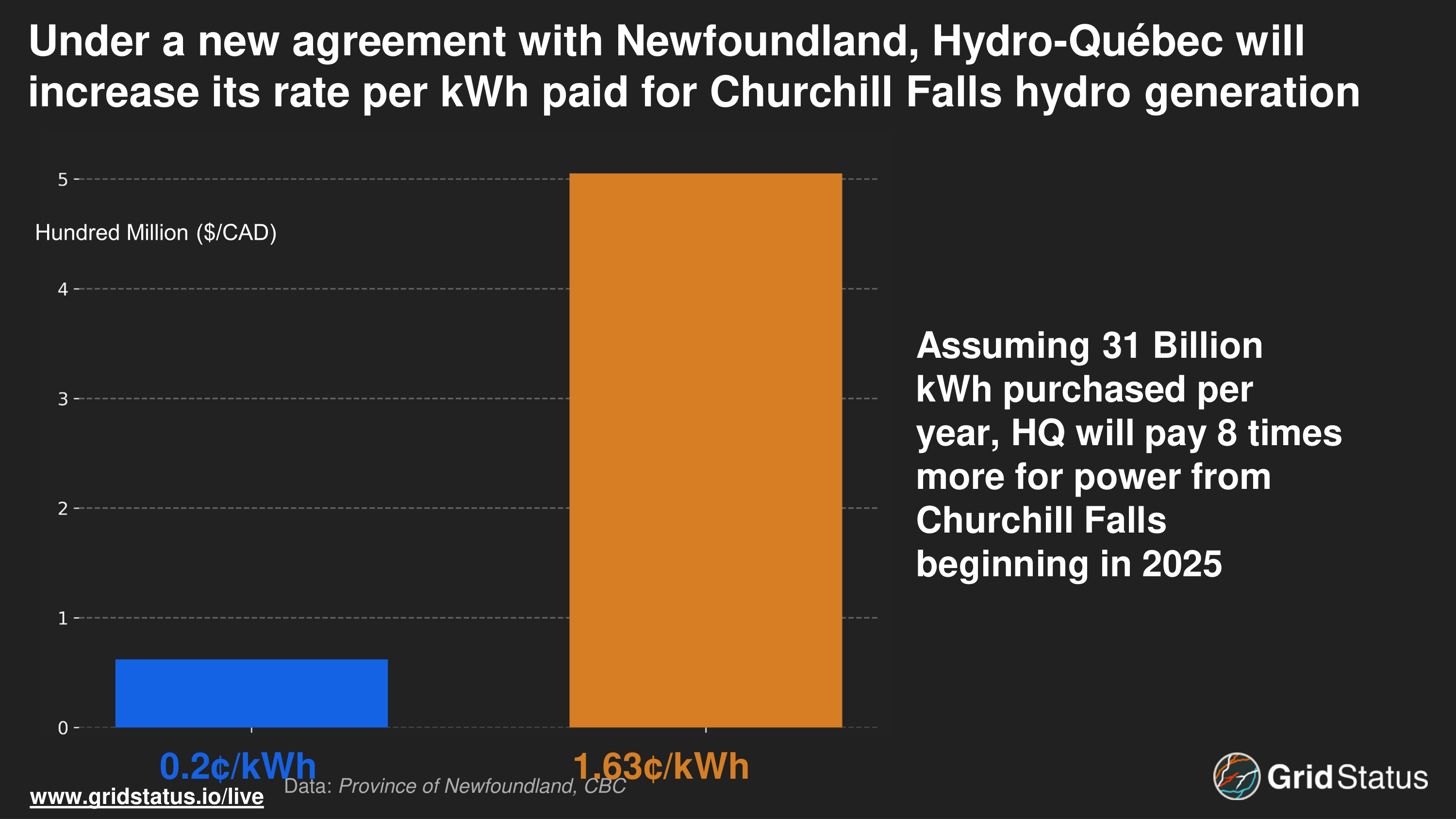

Due to this load growth, Hydro-Québec also plans to increase its existing ties with Newfoundland. In the mid-1960s, HQ signed the Churchill Falls agreement with Newfoundland, a long-term power purchase agreement in the mid-1960s. This agreement allowed HQ to buy nearly 80% of the plant's output at an exceptionally low rate, $0.002/kWh. Québec’s overwhelming use of the plant’s capacity has left Newfoundland's supply increasingly tight, and Québec has profited heavily from the plant.

Before the expiration of this agreement, Québec returned to the table and sought to expand its stake in Churchill while addressing some of the historical wrongs in the original PPA. Under a new agreement between HQ and Newfoundland, Churchill is expected to undergo upgrades to existing generator units, adding 550 MW, expanding the power plant itself for an additional 1,100 MW, and constructing the Gull Island Power Plant at 2,250 MW. Additionally, Quebec will pay more for the power it buys from Churchill, which, according to CBC, will be: “starting at 1.63 cents in 2025, and increasing to 7.84 cents by 2041.”

While beneficial for Newfoundland, the willingness on the part of Québec to return to the table, and pony up to higher costs, shows the province’s need to increase supply.

This increase in payments, based on an estimated 31 billion kWh purchased per year, greatly increases revenues for Newfoundland, averaging over a billion dollars per year by the time the new contract expires in 2041.

The shift to wind and ties with other Canadian provinces illustrate the changing role of Hydro-Québec and wider international cooperation across the Northeast.

Time for the Maritimes

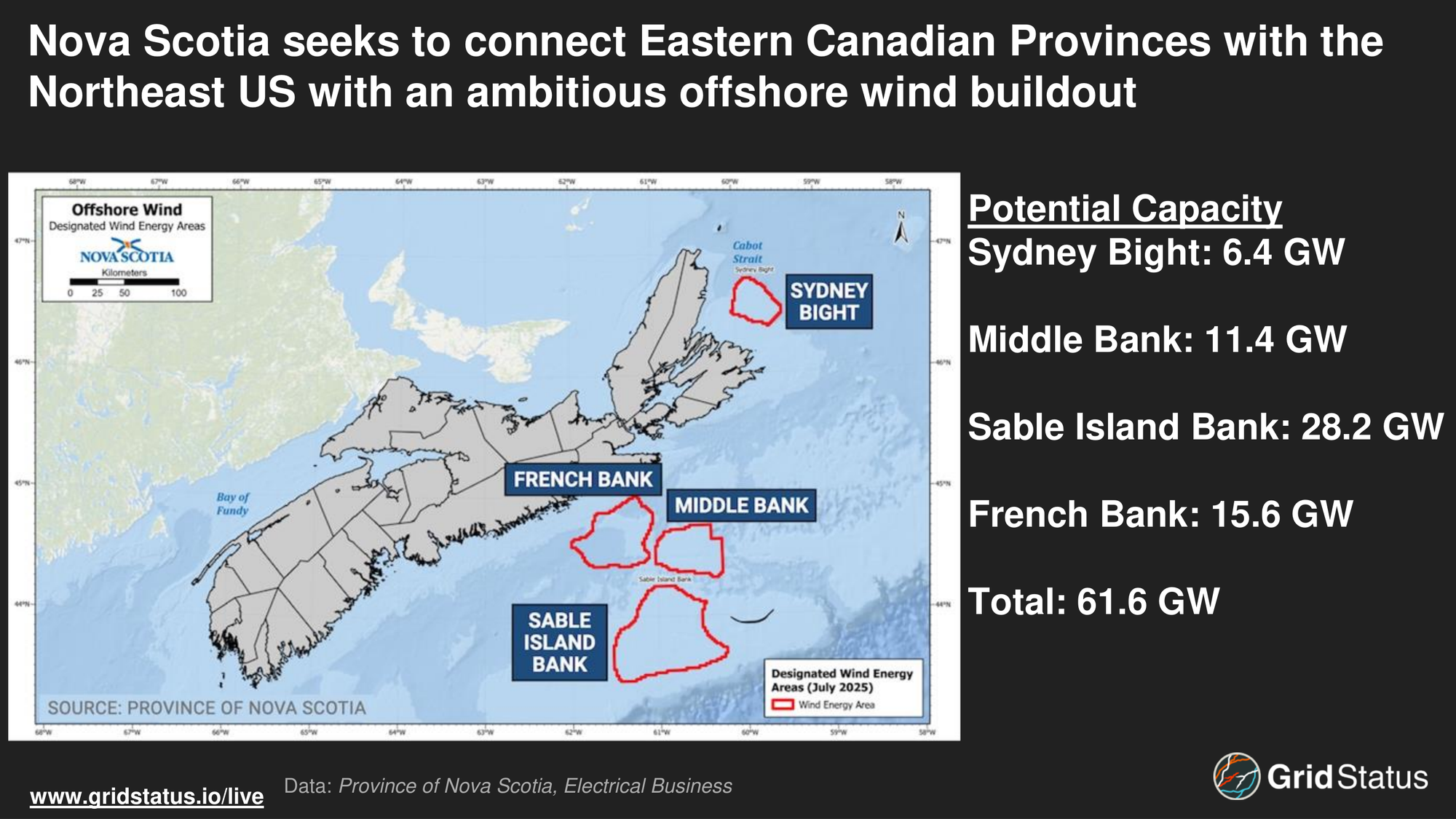

While historically Québec and Ontario have been the provinces of choice for powering the Northeast, New England is already looking elsewhere for future ties with Canada. Nova Scotia Premier Tim Houston has laid out an ambitious offshore wind project, the first in Canadian history, known as Wind West. While the first iteration of the project calls for an already ambitious 5 GW of offshore wind development, in a region where load peaked at a little over 2 GW in 2024, project aspirations envision over 60 GW of wind capacity in some of the highest wind speeds in the world, averaging 10.3 m/s at 100M hub heights.

The potential wind build-out has policy makers on both sides of the border imagining wider ties between Massachusetts, which has had its offshore wind ambitions squashed by the Trump administration and statutory requirements to procure wind, and Nova Scotia.

These deepening ties come amidst a challenging geopolitical situation as threats to annex Canada as the 51st US state are lobbed, and as tariffs, which we wrote about earlier in the year, add uncertainty to cross-border power flows and materials needed to support a wider grid build-out.

As we enter winter, and as the specter of gas constraints in an increasingly tight Northeast reappears, monitor Québec flows and pricing impacts in real time with our dedicated New York and New England live pages.